New FamilySearch Apps Making It Easier to Preserve Family Memories

Contributed By Angelyn Hutchinson, Family Search contributor

Ancestors of author Angelyn Nelson Hutchinson who immigrated from Sweden to Utah in 1902. They are the parents of Herman Nelson mentioned in the article. Family photos are a way for families to connect with their family’s history.

Article Highlights

- Living memories are family stories that individuals carry with them.

- Living memories help provide context for future generations to face challenges.

- FamilySearch is working to make it so everyone can record living memories, no matter their circumstances.

“Knowing your ancestry helps individuals feel a sense of belonging and connectedness in a world that is often disconnected and isolating.” —Amy Harris, BYU historian

Related Links

I heard my father’s voice the other day.

I cried.

The last time I heard it was in 2008. It was fall when Dad died. I miss him every day. His voice sat on my shelf for almost nine years, captured on an old VHS tape that was recently discovered.

In 1990, my father set up his camcorder and videotaped his uncle Herman, the last of my great-grandparents’ seven children. Using old photos, Herman, seated beneath the cottonwood trees in his yard on a summer day, told the story of his parents emigrating in 1901 from Sweden to Cache Valley in northern Utah. He described their lives and struggles and those of other ancestors who were gone but not forgotten to him. The details and stories that I’d never heard unfolded before me nearly three decades later as I watched the video now in my possession, and Herman’s memories became mine.

Living memories: scrapbooks, photos, videos, artifacts, stories

That tape, now transferred to a DVD, is what genealogists call a “living memory.” It’s the family information and stories that individuals can recite off the top of their heads—but perhaps don’t conscientiously preserve or share for future generations. Dad and Herman preserved a piece of our family history for their descendants.

Many people are the self-appointed scrapbookers of their family, creating a memory scrapbook for each member of their immediate family or a dedicated web page where select family milestones or events are highlighted, contributed to, and shared as a family. These typically include photos, videos, artifacts, and documents with fun or insightful narratives. Newer memory software invites the user to add video and audio files to help preserve additional dynamics of a loved one’s life or a family’s history.

“How many of us would be ecstatic if someone in our family had captured the living memory in our family 50 years ago?” asked Brigham Young University historian Amy Harris, who teaches about living memory in her classes on family history. “You might not be able to go back and talk to your parents and grandparents, so you have to start now.”

Many individuals equate genealogy with names, dates, and dusty old records. That can be part of it, but the worth of those memories is much greater. Harris said that family history is the story of “your people, your tribe—it’s of inestimable value knowing who you are, where you came from.”

How do family memories help?

- “Knowing your ancestry helps individuals feel a sense of belonging and connectedness in a world that is often disconnected and isolating,” Harris said.

- “People who know their ancestry, even if it’s not heroic, even if there are skeletons in the closets, have better sociological, psychological, and even financial outcomes in their lives. Teens have fewer behavioral and school problems if they know about their ancestors,” she said.

- Emory University psychologists found in studies that the most resilient children are those who have a strong family narrative.

- If children know their family’s history, they have a greater sense of control over their lives and higher self-esteem.

- New York Times columnist and best-selling author Bruce Feiler, in his 2016 keynote address at RootsTech, emphasized the importance of knowing your ancestry to having a happy, high-functioning family.

“The one secret ingredient that high-functioning families have in common is they talk a lot. They talk about what it means to be part of a family,” said Feiler, whose New York Times columns focus on family life.

Keeping and knowing family memories helps us face challenges

Ron Tanner, senior product manager at FamilySearch International, the world’s largest genealogy organization and a free nonprofit subsidiary of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, said his children know the stories of his family and what it means to be a Tanner.

We understand how others handled problems. “When we see our family, we can see examples of good and examples of bad,” Tanner explained. “They can be examples that help us make better choices and better decisions—either not to be like them or to be like them.”

We heal through remembering and recounting. At times a family historian might find it tricky to preserve an accurate account of someone’s difficulties. Recording or writing something is better than nothing, BYU’s Harris emphasized. However, the best family historians don’t sanitize their accounts but write with compassion about someone’s problems and how they helped or hurt. Harris has had students worry about whether to write about difficulties such as abuse and alcoholism. When they did, “they found healing in family history by not pretending that stuff wasn’t there but by facing it head on,” the professor said.

How do we preserve family memories?

Preserving the family’s living memory is an important bridge between the tradition of oral histories of the past and the official records that mark the milestones of an individual’s life.

In America, Canada, and Europe, the ability to use and access technology usually makes it relatively easy to preserve living memory. Preserving living memory isn’t always as easy where technology isn't economically accessible or records do not exist.

Collect oral genealogies before the “rememberers” are gone

For that reason, FamilySearch has been collecting oral genealogies for 52 years from various cultures. It started with Polynesia in 1965, expanded to Indonesia in 1990, and began its current project in Africa in 2004.

Over the centuries, genealogies and family stories in African villages were passed down through the generations by the designated elders or village “rememberers.” But today those villages are losing population as the youth move to the cities in search of work and a better life.

“The village rememberers are dying off, and because of the urbanization of the youth moving to the cities, no one wants to become a village rememberer. When the village rememberer dies, all that information is lost,” reported Rod DeGiulio, FamilySearch vice president of international relations. FamilySearch helps prevent the information from being lost by interviewing and recording the village elders, preserving their information electronically.

DeGiulio says FamilySearch contracts with a workforce, often college students, in seven African countries to record the elders. FamilySearch plans to expand the project to 13 countries by the end of 2017.

Using a recorder with a built-in camera and GPS, the workers record the genealogies and the coordinates of the location and take a picture of the elder. Since 2004, FamilySearch has added over seven million family-linked names to its online database. “We’ve only scratched the surface,” DeGiulio said, pointing out that Africa has 54 countries.

On average, each worker gathers 700 to 1,200 names from each rememberer interviewed. Last year, FamilySearch workers conducted nearly 3,000 interviews in Africa. This year, FamilySearch increased the budget to be able to conduct 10,000 interviews and plans to continue to scale up collection operations in future years.

The organization’s leaders feel a sense of urgency because the average age of elders being interviewed is 71, while the average age at death for an African male is 55 in the areas where the genealogies are being collected.

DeGiulio shares a comment from a worker that underscores the need for expediency.

“I just came in from the field,” the worker wrote, “and there is a story I need to share. We visited a 95-year-old man who was very receptive. He was able to remember 10 generations of the village for a total of 780 names. They were all lineage-linked in families on the pedigree. We visited him four times before completing his work. We decided to visit the man the following day to say thank you and wrap up a few details. When we went, we were told the man had died peacefully in his sleep the night before, after the work was completed.”

The worker’s experience is not unusual, although sometimes the elder dies before the work is completed, DeGiulio said.

The elders don’t give dates, but recite the names beginning with the oldest remembered ancestor and continuing through the descending generations, he explained.

The race to digitize records that tell the family story

In the cities where there may be historic vital records that can tell a family’s collective story, the records likely go back only to when a country gained its independence, perhaps 80 to 90 years, and the records are often deteriorating due to being stored under poor conditions, DeGiulio said. In its effort to preserve family history, FamilySearch is working to digitize records worldwide, including in Africa.

DeGiulio said the mayor of Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of the Congo recognized the need for preservation and easily agreed to allow the records’ digitization when DeGiulio visited last year. The mayor also agreed because he had been impressed with the humanitarian efforts of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in his country.

Computer technology for developing cultures

When Africans desire to preserve their own living memory and genealogy electronically, they can become stymied by the lack of technology or its limitations.

“More than half the world is not wealthy enough to be connected to the internet. More than half the world is not wealthy enough to be remembered. They pass away, and there is nothing recorded about them, their families, and their ancestors. That’s the challenge—getting out and giving the opportunity to be remembered,” said Tim Cross of FamilySearch.

In the past few years, FamilySearch has investigated alternative ways to reach remote areas. In remote Africa, South America, the Philippines, and Asia, access to the internet is primarily a phone and oftentimes a “feature” phone, Cross said.

Cross described the “feature” phone as similar to the Android flip phones popular more than a decade ago. It might have a browser and a couple of basic apps. Users with feature phones can buy a limited data plan.

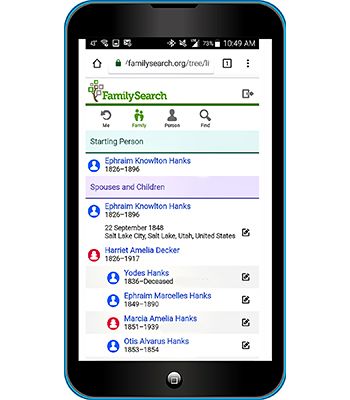

FamilySearch introduced a new version of its Family Tree program, called Family Tree Lite, in April 2017. Family Tree Lite uses a smaller bandwidth, which includes compatibility with the feature phone. To accomplish this reduction, Family Tree Lite eliminated the inclusion of features such as photos and documents that use up data and make it cost prohibitive in many parts of the world to use the FamilySearch Family Tree. Family Tree Lite focuses on recording fundamental or vital family history information (name, key life events, and dates).

Any information added on Family Tree Lite shows up immediately on FamilySearch Family Tree. Users in these remote areas typically do not have personal email addresses. They will be able to ask for FamilySearch’s help or receive FamilySearch communications via a Facebook Messenger BOT.

“It certainly isn’t comprehensive across the world,” Cross said, “but it’s a step in the right direction and an exciting step. It’s hundreds of thousands of individuals gaining access now who didn’t have it before.”

That access means you can now record your living memories even if you live in a country with limited or expensive internet resources and can’t afford internet access or a smartphone data plan. That access means that anyone, regardless of physical or monetary circumstances, can now record the stories of his or her life. You can even sit under cottonwood trees on a summer day and record your family history for your posterity. Your memories don't have to be lost forever.

FamilySearch’s African project is interviewing tribal leaders, known as “rememberers,” to preserve the tribe’s history and family genealogies going back centuries.

FamilySearch’s African project is interviewing tribal leaders, known as “rememberers,” to preserve the tribe’s history and family genealogies going back centuries.

Father of Angelyn Nelson Hutchinson, whose voice she was so touched to hear years after his death in a video interview on VHS tape in the family’s memorabilia.

Author Angelyn Hutchinson was able to make a personal connection with her uncle Herman Nelson from a video interview her father conducted with Uncle Herman while he was still living. It is a treasured family artifact.