How to Manage Your Family's Digital Assets

Contributed By Dick Eastman, Family Search contributor

We can take various steps now to ensure that our family’s digital assets will live on no matter what technology looks like in future years.

Article Highlights

- Aim for at least three copies of information in different digital formats.

- Migrate data to the newest file formats as technology updates.

- Use multiple file formats to save data.

Related Links

In our digitally integrated lives, we create and share most of our pictures and home videos with snazzy digital cameras, incredible smart phones, or other easily portable devices. We download music purchases and perhaps even keep only digital receipts of our purchases through photos or emails.

Someone said, “That [choose your device of choice] is so versatile that it can take pictures, chop celery, and keep us in touch with relatives as far away as Samoa.”

Now that we have all these digital devices, have we figured out what to do with the fruits of those devices—the mounds of digital files and sources we amass daily, weekly, monthly, yearly? What do we do with all our personal digital content that makes up our digital lives?

Most of us have not mastered how to effectively preserve our physical family artifacts. Even more of us are probably at a loss about how to effectively ensure our growing digital treasures are safe in the long term. In this article, we will focus mainly on digital assets.

So the questions remain—what do we back up or preserve and how do we do it? The short answer is that you need a personal digital asset plan.

What do we do with all our personal digital content that makes up our digital lives?

Physical memorabilia

Perhaps we cannot clone physical items, such as family heirlooms, but we can convert them to a digital form that at least makes them easier to share with others and preserves the digital memory of them in the case of physical loss. Perhaps you have a musket that your great-great-grandfather carried in a war or maybe a wooden chest that Great-great-grandma carried with her in a covered wagon across the plains. Heirlooms and other artifacts don’t have to be old. There is reason to preserve digital pictures of the medals your father was awarded for war service or even your children’s report cards.

Keep and store important documents

Like precious tangible family heirlooms, some digital memories, documents, or files also need to be preserved. But how and where do you start? Serious archivists would recommend you subscribe to some variety of the “Backup Rule of Three,” which means you should have at least three copies of your information, on at least two storage media, in three locations (at least one offsite). This redundancy would include a working electronic copy, a readily accessible backup copy, and a backup of your backup.

Should a file be in Microsoft Word (.doc) format or rich text format (rtf)? Or perhaps should it be in ASCII text (.txt) format? My answer would be, “Yes, yes, and yes.” All of the above. The file formats aren’t important as long as your data is migrated to newer technologies as they are developed. One of the more common arguments against saving things digitally is that “the equipment required to read them probably won’t be available in 25 years.” Some of the formats may become obsolete in a few years, but the likelihood that all of today’s formats will become unusable are slim indeed. Once a file has been saved in one format, saving it a second time in a different format typically requires only a few more seconds. At least one of those formats will probably last long enough that the caretaker of your data can later convert it to whatever formats become relevant in the future.

Start by using a simple filing system to document what you have. Just as when you declutter a filing cabinet, you will often find that there are many electronic files you don’t really need or want. Next, protect digital assets you want to keep by making multiple copies of relevant digital files and then storing those copies in as many different locations as possible. Periodically check the files to see if each is still readable. (Can you still open it? Does the data look uncorrupted?) Determine if it should be migrated to some more modern technology that has appeared since the original was created.

Problems facing various storage media

Recent experiences suggest that paper is usually not a good preservation medium and underscore the need to make digital copies. News reports frequently mention earthquakes, tsunamis, hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, building collapses, fires, and other disasters that have destroyed thousands of paper documents in seconds. While not mentioned as often in news stories, burst water pipes can do the same. Paper records can be damaged by mold, mildew, or insects, and they can be discarded by subsequent generations who value the records indifferently. Paper can also deteriorate because of chemicals in the paper, and some inks from pens or printers disappear over time. Because of these kinds of problems, digital copies of paper documents should be made.

However, digital archives have their own set of problems and solutions. Hard drives and flash drives crash, computers occasionally erase data, web-based data centers are occasionally destroyed in major disasters, and sometimes files become obsolete by the latest changes in technical standards. Probably the biggest cause of the loss of electronic personal data is the “oops factor”—the accidental loss of files when we unintentionally delete them and have neglected to make adequate backup copies.

Digital archives have their own set of problems and solutions. For example, hard drives and flash drives crash and computers occasionally erase data.

Punch cards, John F. Kennedy, and the National Opinion Research Center

Bill LeFurgy provides a historical example of these problems in a digital preservation article published by the Library of Congress. A survey of citizen reactions to President John F. Kennedy's assassination was conducted from November 26 through December 3, 1963, by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago. The survey results were recorded on the latest technology at the time—paper punch cards. The data from the cards were input into the mainframe computer used to tabulate study data. Summary results were then published.

Forty years later, following another national tragedy on September 11, 2001, with terrorist attacks in the United States, NORC researchers wanted to replicate the 1963 study by asking the same kinds of questions to assess public reaction. The aim was to compare how the nation responded to two very different tragedies. There was one problem—how to read the punched cards from the 1963 study.

The 38-year-old stacks of 80-column punch cards were still available—no problem there. But finding a card reader machine to read that information from a foregone era was a problem. Fortunately, a vendor was found who could still read the cards and convert them to more modern media. Personnel reported that they “had to refurb [their] punched card equipment; it had been sitting around so long it got a little rusty.” In the end, all worked well. The data was successfully migrated to a readable, modern data format so that the comparison studies could be made. This story, fortunately, had a happy ending.

We face a similar dilemma at home today with the storage media we use for our photos, correspondence, games, and a host of other personal electronic files. If we want to ensure that we can read or access today’s data in future years, we need to migrate them periodically with evolving technologies.

In the case of the 80-column punch cards, the information professionals at the Social Security Administration continue to do that. The punch cards were copied to tape while both tape and card equipment were plentiful. Later, the information was copied from tape to disk and then to newer and more modern disks, and, in the future, they will hopefully be copied to whatever storage media makes sense at that time.

In theory, digital data can be preserved for centuries, far longer than anything stored on paper, punch cards, or even microfilm. You just have to commit to migrating it. Indeed, there are problems with changing technology, but a little education can let us know how and when to take care of this problem, and in the end, it is not difficult.

CAPTION.

Storage worthiness of preservation media

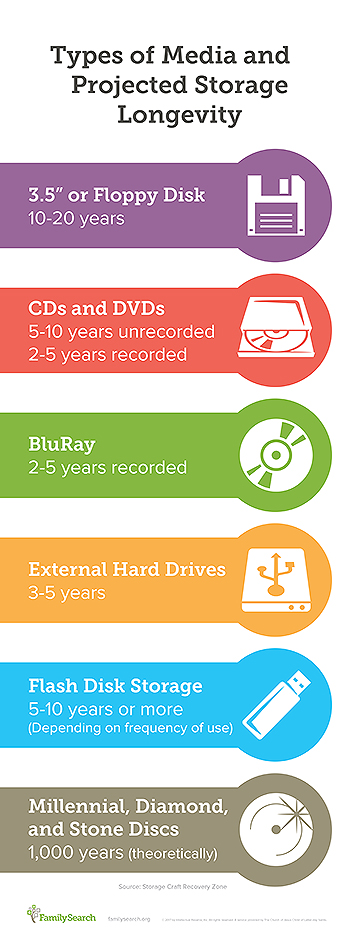

How long will it last?

Rick Laxman, Sr. Digital Preservation Planner for the digital content stored in the Granite Mountain Records Vault, says most consumers would be surprised to know just how quickly their data begins to deteriorate on some of the more popular consumer storage technology. For example, external hard drives, if stored correctly and used sparingly, might last a decade or a little more. Otherwise, you’re looking at 3–5 years of useful storage life.

The outlook can be even bleaker for old floppy or 3.5“ discs. And how about all those CDs, DVDs, and flash drives you’ve been using as your long-term storage solutions? Try 2–10 years, depending on use and how they’ve been stored.

On the other hand, write-once optical discs, such as Millenniatta’s M-Disc or DVD+R are proposed to last 1,000 years. A challenge is that they may require special equipment to record to them, and they can be slow to save to and must be stored properly to yield optimal results.

Types of popular media and projected storage longevity

Laxman suggests that even if we have been astute about storing our electronic files over the years, the average consumer needs to keep up with the technology to retrieve or read data on storage devices they commonly used 10 years ago. For example, how many of us have 3.5” floppy drives, flash drives, or even CD or DVD drives with personal data stored on them? The latest laptops and portable devices don’t even have ports for accessing these storage media as standard equipment. Technology is rapidly evolving. However, those who use these devices are usually aware of updates and can discover from the providers how to change the information from one device to another.

Online storage options are growing in popularity. They offer ease-of-use, ready access, and cheap annual fees as part of off-site preservation options. Many of them even offer free storage for modest amounts of data. Of course, the idea is that once you’ve grown accustomed to the value of your off-site backup, you’ll be willing to pay for more features and capacity. That said, the annual cost is still minimal compared to the benefits.1, 2

Unrecorded CDs last 5-10 years, but only 2–3 years if you've recorded data on them.

A personal digital asset plan: five simple steps

.jpg)

The five simple steps to a personal digital asset plan.

How do we track all our electronic records? We need to consider a personal digital asset plan. Know what you have, where it is stored, and how it will be taken care of in the future. Obviously, this plan doesn’t need to be developed all at once. Pat Dorff in her book File—Don’t Pile! recommends the following five simple steps: 3

1. Identify what you have on your storage devices.

Make a general spreadsheet or list of what you have and where. You might decide to focus on certain types of records, such as pictures, videos, or documents. Consider where they are located. For example, they may be located on your phone, a hard disk, a flash drive, an I-Pad, laptop, and so on. Once you’ve noted all records by a type (such as photos), then identify other categories, such as those found in this list from the Digital Preservation Coalition.

2. Determine what you want to save.

Which categories do you value the most—photographs, videos, social media posts, correspondence, and so on? What kinds of files do you want to save?

3. Organize the content.

Place all the files you want to preserve on one hard drive to start. If possible, make a logical folder and substructure to help you locate files in the future. For example, you could indicate what is significant about a file or folder of files and then organize subfolders by date (for example, “Family Vacations” might be your broader category, and then you could organize subfolders by year, such as “2010-17”). Consider what descriptive information you need to include to help you retrieve or understand the content a few decades from now. Make the file and folder names as long as they need to be to adequately represent the content of the files and folders.

4. Make copies and manage them in different places.

It requires very little digital and physical space to store the equivalents of thousands of books. The wise consumer does not settle on any single solution. Remember the LOCKSS principle of saving—Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe. If you keep copies of your files in various places, not all of your important files can be destroyed in one calamitous event. You will always have copies.

5. Manage your content over time. Make sure you have the proper technology to read what you have saved.

Test your stored content periodically to ensure it is accessible and legible with current technology and newer programs, or determine if it needs to be migrated to more modern storage. Also address temperature and humidity concerns. If a room is comfortable for human habitation, it should also be good for computer equipment and storage media. If you need to know where and how to store all these copies of electronic media in a more archival way, see the suggestions listed by the Minnesota Historical Society, one of many sources online.

As a rule of thumb, remember that unless something is restricted by copyright, we are free to make all sorts of digital copies, something that is easy and cheap today. Even better, we can store digital copies in all sorts of locations: somewhere in our home, at a cousin’s house, and in data centers in Rio de Janeiro, Cape Town, and Mumbai. In fact, we can store any digital files in seven or more data centers that are in seven or more locations around the globe. What are the odds that ALL the copies will be destroyed? None.

Find peace in your decisions

I have heard variations of this story dozens of times, and I bet you have, too. A family member spends thousands of hours researching and compiling a family tree or creating a life story through photos and narratives and perhaps even publishes it. When the person dies, well-meaning but disinterested relatives clean out his or her belongings and throw all the family history information and perhaps old family photographs into a nearby dumpster.

Ideally, you should digitize such lifetime works throughout your life and make sure that a family member, friend, or society that shares your interest knows how to retrieve your copies after you are gone. Even better, simply give these people copies while you are still alive and ask them to copy the files to newer formats every few years. If your data vaporizes soon after your death, who cares? Your information would already be in the hands of multiple members of a younger generation. If files are password protected, make sure those passwords are passed on to the persons who currently have access to the files.

Make sure that an interested family member or person will be able to access your data stored online for some time after your demise and then will be able to make copies for future family members.

A bad scenario is one where digital data is set aside and ignored for years. You need to make sure your new caretaker has an interest in preserving your work and will periodically convert it to whatever file and physical formats become popular in the future. In short, preserving data for centuries is possible by using a combination of technologies and by some advanced planning. Remember, preservation is a process, not a technology or media. Isn’t it worthwhile to preserve the results of the hours, days, and years you spent gathering that information?

Starting today, I plan never to write again “Which storage medium is best?” My answer is, “Yes.” That is “yes,” as in, “all of them.” Don't store a single copy of anything and expect it to last. It makes no difference if that single copy is on paper, a computer, a flash drive, or a disc. A single copy of anything is at high risk of loss. Whether we are talking about a major archive of an entire nation or about your family’s photographs of Aunt Tilley as a child, there really is but one reliable form of preservation insurance—having multiple copies on different kinds of media, all stored in different locations.

Flash drives can last 5–10 years depending on how much you use them.