Joseph Smith’s Unsuccessful Visit to White House for Redress Still Inspiring, Editor Says

Contributed By R. Scott Lloyd, Church News staff writer

Left: My Dear Beloved Companion: Letters of Joseph and Emma, painting by Michael Malm. Right: Photograph of handwritten letter from Joseph Smith to his wife Emma, sent from Springfield, Illinois, in October 1839, while he was en route to Washington, D.C.

Article Highlights

- The failed trip to Washington showed Joseph Smith that he couldn’t depend on outside government agencies for help.

- Joseph’s resilience and perseverance is the encouraging moral of the story.

“I love these letters, not only for what they tell us about Joseph and Emma, but these letters grant us a glimpse into the way that Joseph and Emma Smith communicated with each other about issues such as parenting.” —Spencer W. McBride, Joseph Smith Papers editor

It was late October 1839, an inopportune time for Joseph Smith to be journeying to Washington, D.C.—or anywhere else.

His little son Frederick lay sick at home in Commerce—soon to be renamed Nauvoo—Illinois, where many of his people, having recently been driven from Missouri, were struggling to rebuild their lives. Many were seriously ill.

In addition to caring for her ill son and her family, Joseph’s wife Emma was providing care in her home for those who needed it.

“There’s something heart-wrenching, when I read Joseph Smith’s letter to Emma shortly after he left, and he talks about how it hurt his heart to leave little Frederick behind in that condition,” said Spencer W. McBride, one of four volume editors of the latest Joseph Smith Papers volume, Documents, Vol. 7.

“We really get the sense of how it weighed on Joseph Smith when we read the letters that he wrote to Emma,” said McBride at an April 19 lecture in the Assembly Hall on Temple Square, where he addressed the topic “Joseph Smith in the White House,” exploring Joseph’s 1839 trip to Washington. “And this is actually a very fortuitous result of his trip. In the entire corpus of Joseph Smith documents, there are not very many letters between Joseph and Emma. … But by leaving Nauvoo, this creates the need to generate new documents, letters that Joseph writes to Emma and that Emma writes to Joseph.”

McBride quoted this passage from Joseph’s letter, written from Springfield, Illinois, en route to the nation’s capital: “It will be a long and lonesome time during my absence from you, and nothing but a sense of humanity could have urged me on to so great a sacrifice. But shall I see so many perish and not seek redress? No. I will try this once in the name of the Lord. Therefore, be patient until I come, and do the best you can.”

U.S. President Martin Van Buren from an original drawing by Daniel Dickinson. Joseph Smith visited him in 1839 in a quest for redress from the federal government for wrongs inflicted on the Latter-day Saints in the state of Missouri. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Poignantly, the prophet adds: “I cannot write what I want, but believe me, my feelings are of the best kind towards you. My hand cramps, so I must close.”

Writing back a month later, Emma encourages Joseph on his political mission and updates him on the health of their children (Frederick has recovered, but Joseph III has now taken ill).

She closes by writing, “The day is waning and night is approaching so fast that I must reserve my better feelings until I have a better chance to express them.”

“I love these letters,” McBride remarked, “not only for what they tell us about Joseph and Emma, but these letters grant us a glimpse into the way that Joseph and Emma Smith communicated with each other about issues such as parenting.”

By stagecoach, Joseph arrived in Washington on November 28, accompanied by Eilias Higbee, checking into the cheapest boardinghouse they could find, McBride recounted.

Illinois congressman John Reynolds had agreed to introduce them at the White House, and they go with him the next day to see U.S. President Martin Van Buren.

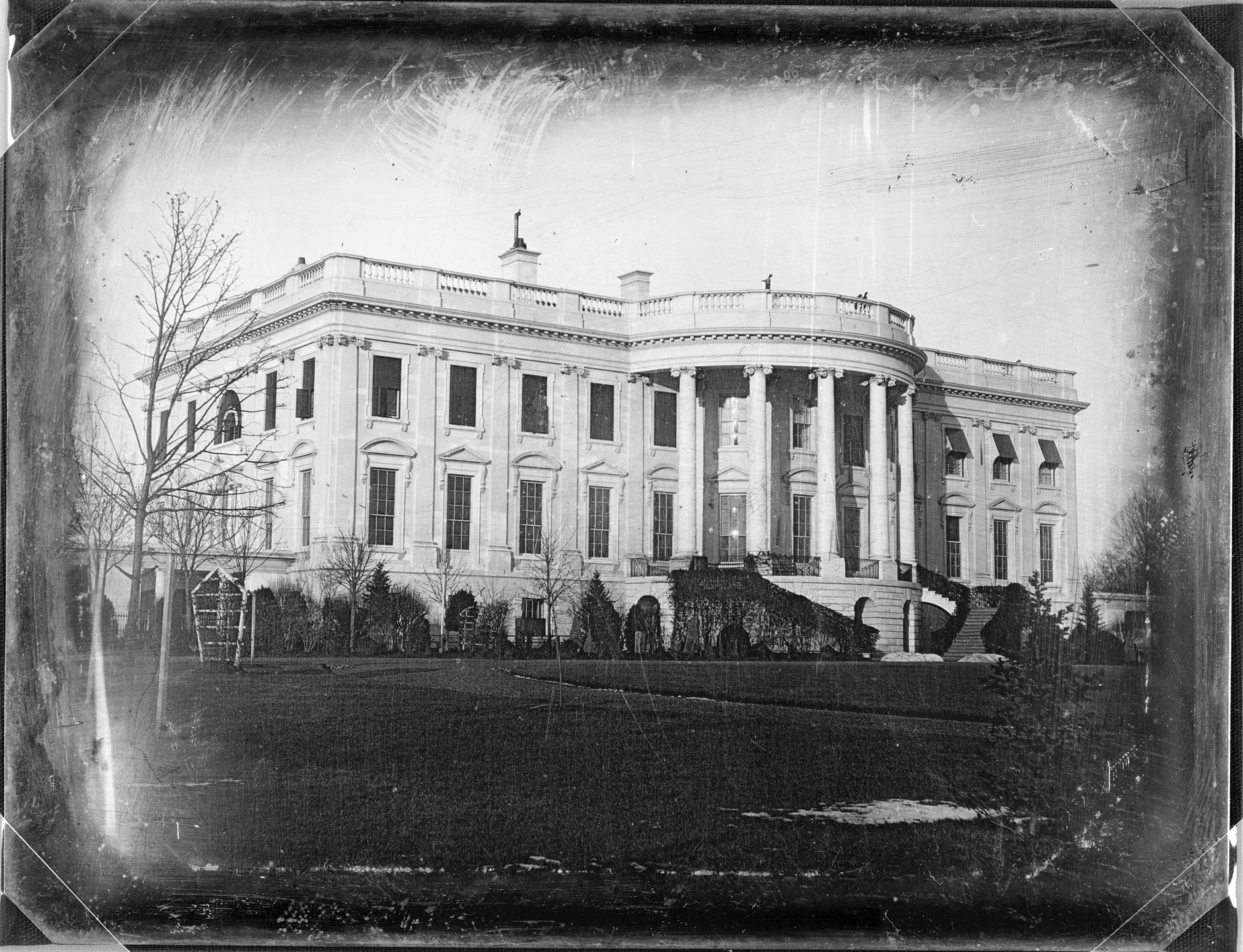

“We found a very large and splendid palace surrounded by a pleasant enclosure decorated with all the fineries and elegancies of the world,” the Prophet wrote.

“And then he said that he felt at home in the White House, that he had a perfect right there, as much right as Van Buren, because the house belonged to the people,” McBride said.

It was not a private audience with the U.S. president, as has been supposed. Rather Van Buren would hold receptions almost daily, just outside his office, and the Mormon representatives were obliged to compete for his attention inside a crowded parlor.

Reading a letter of introduction that had been written for them by prominent officials in the West, Van Buren put it down in frustration and reportedly said, “What can I do? I can do nothing for you. If I help you, I will come in contact with the whole state of Missouri.”

Spencer W. McBricde, a volume editor of the Joseph Smith Papers project, speaks to an audience in the Assembly Hall on Temple Square about Joseph Smith’s 1839 visit to the White House in Washington, D.C. Photo by R. Scott Lloyd.

Van Buren did not have a history of religious prejudice, McBride said, but it was for electoral reasons that he declined to help the Mormons.

Nevertheless, he did agree to reconsider, and the Church leaders left with the hope that he would favorably mention them in his upcoming annual message to Congress.

That, McBride said, appears to be the primary reason for the visit to Van Buren, for they were about to deliver a petition, or “memorial” to the lawmaking body seeking redress and $2 million in reparations for the wrongs that had been inflicted upon the Church members in Missouri.

In this, they were disappointed, both by Van Buren and by the Senate Judiciary Committee, which determined that Congress had no jurisdiction in the matter but that the Church members should take their case to the Missouri government or the courts in that state.

“And so this was devastating to the Mormons,” McBride commented. “But what made it even worse was the language of the committee’s report. It reads: ‘The petitioners may if they see proper apply to the justice and magnanimity of the state of Missouri, an appeal which the committee feels justified in believing will never be made in vain by the injured or oppressed.’

“Talk about the wrong thing to say to a people who had just been kicked out of Missouri!”

An impact of the experience, McBride said, was that in designing the charter for the new city of Nauvoo, Joseph reserved considerable powers. “Most of these powers—having a militia, a university, the right to hear arrest charges and issue writs of habeas corpus—existed in other Illinois cities at the time. But what made the Nauvoo charter so controversial was that it contained all those rights together. It was the aggregation of those powers that contributed to the outcry against the Mormons in Nauvoo.”

In the context of the trip to Washington, it can be seen that Joseph realized he couldn’t depend on outside government agencies for help and that he needed to find another way to protect his people, McBride noted.

Despite the visit to Washington not having a happy ending, there is an encouraging note to be drawn from the episode, he said. “In Joseph, we see a man deeply committed to his beliefs, a man who endured severe conditions to protect the men and women who followed him. As a prophet, he was true to his convictions, and he was buoyed by his faith in God. To see such conviction, to witness such faith by those men and women who came before us, is something that should inspire us. Maybe, just maybe, Smith’s resilience amid difficulties and his perseverance in the face of repeated rejection is the encouraging moral of the story.”

The White House as seen in 1846, about seven years after Joseph Smith visited U.S. President Martin Van Buren there. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Handwritten letter from Joseph Smith to his wife Emma, sent from Springfield, Illinois, in October 1839, while he was en route to Washington, D.C. Photo by R. Scott Lloyd.