Cartographer Uses Maps, Animated Timeline to Tell Story of 1846 Pioneer Trek

Contributed By R. Scott Lloyd, Church News staff writer

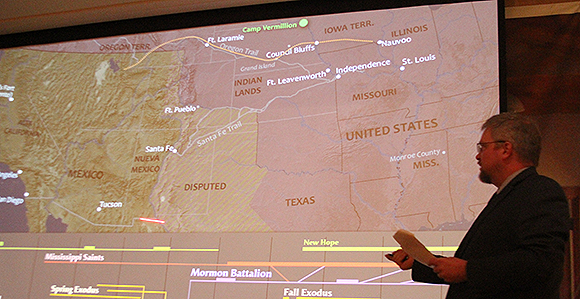

Historical cartographer Brandon S. Plewe presents an animated map and timeline to tell the story of the Mormon pioneer exodus of 1846 during his presentation at the Church History Museum January 19, 2018.

Article Highlights

- Challenges prepared Saints to settle the western wilderness.

“It is a story fraught with unforeseen obstacles and frequent failure. But these challenges result in a community that is better prepared for a successful exodus to and settlement in the western wilderness.” —Brandon S. Plewe, historical cartographer

Related Links

The Mormon pioneers’ exodus from Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1846 is not the story of one pioneer trek, but rather a dozen pioneer treks that interconnect with and intersect each other over hundreds of miles.

So says Brandon S. Plewe, a historical cartographer who has used maps, graphics, and timelines to help him make sense of the epic pioneer trek in which thousands of Latter-day Saints fled mob oppression and found refuge in the Salt Lake Valley.

“I’m intrigued with the past but when I read books, I get lost,” Plewe told an audience gathered January 19 at the Church History Museum for the latest in the monthly Evenings at the Museum event. “I’m a visual thinker, so I figured if maps and graphics and timelines and what-not help me understand the past better, maybe they can help other people understand the past better.”

To that end, Plewe, who holds advanced degrees in geography and has done research in historical cartography, presented to the audience an animated map and timeline showing the various elements of the 1846 exodus. His video progressed along the timeline at the rate of six seconds for each day in 1846, with map elements representing the various groups changing as the progression continued.

He said he selected 1846 for his presentation because that year is a prologue of sorts to the Mormon pioneer trek. “As Nauvoo is evacuated, and despite the intentions of Brigham Young and the Twelve to lead the Saints to their new home in the West in a nice, orderly fashion, people seemed to end up going every which way. It is a story fraught with unforeseen obstacles and frequent failure. But these challenges result in a community that is better prepared for a successful exodus to and settlement in the western wilderness.”

A textual description does not do justice to the experience. Nevertheless, here are some month-by-month highlights of Plewe’s narrative.

January

Nauvoo, on the Illinois border with Iowa, is at the edge of the existing United States.

“As the year begins, there are about 15,000 Mormons in Nauvoo and the immediate area,” he said. “Some have chosen to follow other claimants to Church leadership or are drifting away from the faith altogether, but most plan to follow the Twelve.”

Brigham Young, the Twelve, and the Council of Fifty have spent months evaluating maps to formulate a plan. Several members of the Twelve would lead a small scout company, called the Camp of Israel, across a thousand miles or so to the West to find a new territory for settlement.

The rest of the Saints would come behind, forming a temporary camp somewhere along the trail, probably at the Grand Island of the Platte River in present-day Nebraska.

One member, John Brown, received permission to return to his wife’s family in Mississippi and form a pioneer company of the several branches there. They would meet the Saints along the trail somewhere, hopefully at Grand Island.

Some of the Saints have already gone west. James Emmett, a member of the Council of Fifty, volunteered to lead an exploring expedition to the West. He led a company of nearly 200 to Camp Vermillion in present-day South Dakota.

February

The Church is exploring other options for gathering the Saints. One option for those on the U.S. eastern seaboard is to sail around North America to California. Sam Brannan, a Church leader in New York, charters the entire ship Brooklyn for this purpose.

The Brooklyn embarks from its namesake port on February 4 with 240 Mormons gathered from across the eastern United States.

The Brooklyn, which embarked from its namesake port on February 4 with 240 Mormons.

The ship Brooklyn traveled 24,000 miles from New York to San Francisco.

In Nauvoo, the Camp of Israel begins gathering at Sugar Creek in Iowa, across the Mississippi River. Departure is delayed after the frozen river thaws and when the Twelve are frequently called back to deal with issues that can’t be delegated.

By the time the Camp of Israel embarks at the end of February, it has grown from an express of 300 men to almost 2,000 people in 400 wagons. Church leaders still have only a vague idea of where they are going.

“Thanks to the mob, this is clearly a rush job,” said Plewe.

At Camp Vermillion, several families are fed up with James Emmett’s leadership style and have left for the South, hoping to run into the main body of Mormons along the way.

March

The Saints aboard the Brooklyn are beset by major storms, including one that almost wrecks them off the coast of the Cape Verde Islands near Africa.

“This route going clear across the Atlantic to Africa to get to South America may seem rather roundabout, but this was the normal route … because you could take advantage of the dominant wind and ocean currents,” Plewe said.

For the Camp of Israel, after a week of travel, it is clear the company is unwieldy and unorganized and that many are not prepared for the journey. Brigham Young reorganizes the company, several people get work for a short time, and others decide to stay back until they are better prepared.

The leaders formulate what they think is a more pragmatic plan, deciding to go south into Missouri, likely aiming for a trailhead of the Oregon Trail.

John L. Butler in the Camp of Israel had been a member of the Emmett’s Vermillion Camp. He receives permission to ride ahead and try to persuade Emmett to bring the camp south to meet the rest of the company.

Butler and James Cummings head northwest, following a route that will turn out to be followed by the rest of the Saints.

April

The plan for the Camp of Israel to go into Missouri is deemed unworkable due to trail conditions. Brigham Young is increasingly worried about returning to Missouri, where the Church had suffered severe oppression.

They return to the original plan to cross Iowa toward the Council Bluffs area.

“At the literal and spiritual low point of the trail is where William Clayton writes the hymn ‘Come, Come, Ye Saints,’” Plewe noted.

In Monroe County, Mississippi, John Brown sets forth from his in-laws’ home with a company of 14 families from several branches in Mississippi and Alabama who had already been preparing to leave. His own family will stay behind and prepare to emigrate the next year.

Butler and Cummings reach Council Bluffs, where they find the families who had left Emmett. They give them the good news of the approaching Camp of Israel but, unaware of the change in destination, send the families down to Missouri to wait for the camp.

Scouts are sent ahead from the Camp of Israel to find places of temporary settlement. One is established in Iowa and named Garden Grove. By year’s end, about 600 people will be living there.

The Brooklyn has made good time and reaches the most perilous part of the journey, rounding Cape Horn. Disease, especially scurvy, begins to set in.

Mormon settlements in Council Bluffs, Iowa, 1846–1853.

May

Butler and Cummings reach the Vermillion camp. Emmett is not in camp, and they convince his followers to join the main body of the Saints downstream. They rejoin the main body, now at the Iowa-Missouri border.

The Brooklyn, having been blown off course, finds its way to Juan Fernandez Island and resupplies there, much more cheaply than they could have done at Valparaiso, Chile.

Back in Nauvoo, Apostle Orson Hyde dedicates the Nauvoo Temple on May 1. “Ironically, completing this centerpiece of the City of Joseph marks the official end of the Mormon sojourn there. At least the Saints could say they carried out Joseph Smith’s final wishes.”

Elder Hyde and Elder Wilford Woodruff leave to rejoin the rest of the Twelve.

At the end of May, a second and larger way station is built in Iowa and called Mount Pisgah, becoming the larger way station with about 1,000 residents by December.

June

Scouts are being sent ahead but also returning east to find better routes from Nauvoo.

The pioneers from Mississippi have reached Independence, Missouri, having traveled almost four times as much distance as the Saints in Iowa in less time by following established roads.

As the United States war with Mexico heats up, Jesse C. Little, the Eastern States Mission president, and his new friend Thomas L. Kane are in Washington, D.C., lobbying for support for the Mormon exodus. In response, U.S. President James Polk sends Captain James Allen to Iowa with a commission to raise a battalion of 500 Mormons to join the U.S. Army.

John Brown and his company reach Grand Island, where they were supposed to meet Brigham Young, who is not there. They continue up the Oregon Trail looking for the Camp of Israel, which, 150 miles behind them, has finally reached Council Bluffs after a four-month slog, with diminished hopes of reaching the Mountain West that year.

Orson Hyde arrives in Council Bluffs only two days later after a journey of only a month on the new roads.

The Mormons secure permission from federal Indian agents to settle on one or both sides of the Missouri River.

As Nauvoo is evacuated, thousands of Saints are in motion. At least 1,500 take the Mississippi River to St. Louis, Missouri, where there are jobs, a strong Church organization, and riverboats going up the river toward Council Bluffs.

Hundreds more scatter throughout the towns and villages of eastern Iowa looking for jobs.

By midsummer, the 10 miles along the trail toward Council Bluffs becomes the “Grand Encampment,” littered with thousands of wagons.

The Brooklyn has reached the Sandwich Islands (now Hawaii) to deliver a load of freight the ship had brought from New York.

July

After several delays, Brigham Young and other Apostles take their wagons across the river and set up camp at Cold Spring, planning to move on. But they must spend the next several weeks back in Iowa recruiting soldiers for the Mormon Battalion. They organize the Church with a high council and 80-plus bishops to take care of the soldiers’ families.

Five hundred miles ahead, the Mississippi company are dismayed at frequent reports from eastbound travelers that there are no Mormons ahead. As they approach Fort Laramie in present-day Wyoming, a mountain man invites them to spend the winter with him and other trappers at Fort Pueblo in present-day Colorado.

After three weeks of heavy recruiting, Mormon Battalion soldiers parade out of camp in grand fashion.

The 11 available Apostles hold a council and officially decide to winter there until spring, abandoning their initial plan to go west in 1846.

The Brooklyn completes its voyage, sailing into Yerba Buena (present-day San Francisco) after six months and 24,000 miles. The 240 Saints double the size of the town.

August

The Mormon Battalion marches into Fort Leavenworth in present-day Kansas, where the soldiers are outfitted, formally organized, and paid. Soon after they depart down the Santa Fe Trail, their well-liked leader James Allen dies. His replacement, Lt. Andrew Jackson Smith is far less popular.

Four Apostles depart on their missions, three floating downstream toward New Orleans to board a ship. They meet the battalion at Fort Leavenworth and receive the soldiers’ pay, which Elder Parley Pratt takes back to Council Bluffs. He then takes an overland route through Nauvoo, Chicago, and New York, meeting his brethren in Liverpool, England.

On the east side of the Missouri River, the Saints are beginning to leave the Grand Encampment to build winter settlements wherever they can find water, timber, and farmland. By year’s end, dozens of clusters will be scattered over 50 miles.

The Mississippi company has reached its wintering site at Fort Pueblo. They wonder what has happened to everyone else. It is nine months since they have heard from the Church.

September

John Brown leads a small group of men east along the Santa Fe Trail to find Brigham Young.

Nauvoo by now is almost empty, with only a few of the oldest, poorest, and sickest Saints remaining. They are driven out of the city by the mob. With no resources to cross Iowa, hundreds of refugees camp at Potter’s Slough, directly across the river.

News of this reaches Council Bluffs. A rescue company of 25 wagons is formed and heads east. Additional companies will depart soon afterward from the east bank and from Garden Grove.

John Brown encounters the Mormon Battalion along the Santa Fe Trail. They inform Brown that the main company is wintering at Council Bluffs, and Brown tells them of his nearby camp at Pueblo. A sick detachment is sent west to Pueblo while the battalion heads south.

At Council Bluffs a good settlement site overlooking the Missouri River is selected. This new “Winter Quarters” is surveyed, and pioneers from both sides of the river begin building cabins. By year’s end, 3,800 Saints will be living in this temporary city.

October

John Brown returns home to Mississippi. The next year, he will lead a second Mississippi company west in time to meet Brigham Young’s advance party en route to the Salt Lake Valley.

The rescue company has reached the Mississippi River, where they find the refugees without adequate clothing or food. Awaking the morning of October 9, the refugees and rescuers are astonished to find flocks of quail lighting in the camp.

“This ‘miracle of the quail’ nourishes them both spiritually and physically, preparing them for the journey west,” Plewe said.

The Mormon Battalion reaches Santa Fe, New Mexico. Col. Phillip St. George Cook, more popular with the soldiers than Smith had been, takes command of the battalion. They send another detachment back to Pueblo, including most of the remaining women and children who traveled with the soldiers.

In California, Sam Brannan and his Brooklyn voyagers are convinced Brigham Young will be bringing the pioneers there the next year, so they create a settlement they call New Hope. The next year, Brigham makes it clear he has no intention of locating near other settlements again. Most of the Brooklyn Saints eventually move to Utah.

November

As Winter Quarters grows, the high council divides it into 22 wards, each with a bishop, as in Nauvoo. At first, the wards are merely districts to collect tithing and use it to care for the poor and widows, but the bishops are soon given more authority to hold school, execute the estates of dying members, conduct disciplinary courts, manage membership records, and hold separate Sunday meetings.

“For the first time, the modern ward briefly appears,” Plewe said.

The Mormon Battalion at Williamsburg in southern New Mexico sends one last sick detachment back to Pueblo before it leaves the territory. Over the year, Fort Pueblo will house 100 Mississippi Saints and about 200 from the battalion. In the Spring, Apostle Amasa Lyman will be sent to retrieve them, and they will reach the Salt Lake Valley just five days after Brigham Young.

Three rescue companies return to western Iowa and reunite the poor Saints with their friends and families.

“It’s striking to realize at this point that the entire midwestern Church is essentially homeless,” Plewe said. “Unfortunately, they have settled in most of these sites too late to raise crops to store, so we shouldn’t be surprised when sickness, hunger, and death stock the camps that winter. Their survival is largely dependent on frequent trips to towns in northern Missouri to buy or trade for supplies or to work.”

The battalion has turned west into the trackless wilderness, commissioned to pioneer a wagon road between the Rio Grande and California. It will become the major route for southerners to reach the California gold fields in 1849.

December

As the battalion follows the San Pedro River near modern Sierra Vista, Arizona, they are caught in a stampede of feral cattle. It being the closest thing they will ever see to combat, they sarcastically brand it “the battle of the bulls.”

On the 16th, the battalion reaches Tucson expecting to fight. However, the Mexican soldiers have retreated. They wait for the battalion to pass through town and then reoccupy the city.

By year’s end the battalion is traveling down the Gila River just southwest of the future Phoenix.

“I hope this experience helps you see the big picture of this year,” Plewe said in conclusion, “how all these various stories fit together into a single drama playing out in space and time. Our understanding of this or any other historical event is incomplete without this appreciation.”

He said one could reach the conclusion that 1846 was a year of failure. “In December, nobody in this story is where they intended to be in January or where they wanted to be.

“However, you could also reach the conclusion that they were exactly where they needed to be. The Twelve and the general membership were clearly not ready for a transcontinental journey in February 1846. … But they were ready in February 1847 thanks to the hard lessons they had learned and the revelation they received in January 1847 that they called “the Word and Will of the Lord,” now Doctrine and Covenants 136, that brought those lessons home.”

The amazingly successful pioneer experience of the next 22 years can be attributed to the pioneer experience of 1846, he said. “I, for one, am grateful for what they went through on my behalf.”

The Church History Museum offers maps and interactive displays in its recently opened exhibit Mormon Trails: Pioneer Pathways to Zion, 1846–90, developed with Plewe’s assistance.