Protecting Religious Freedom Is a Divine Obligation

Contributed By Jason Swensen, Church News staff writer

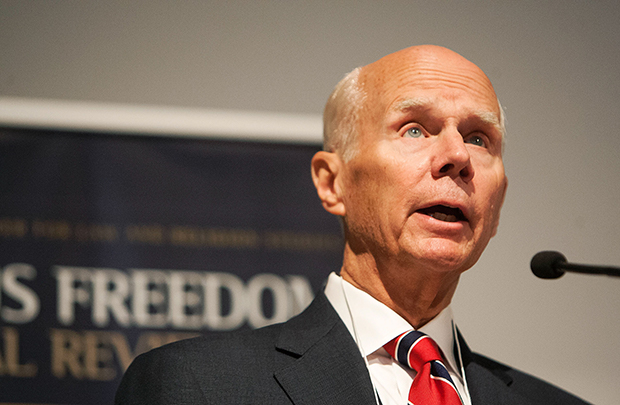

Elder Lance B. Wickman, general counsel of the Church, gives his keynote speech at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016.

Article Highlights

- Threats to religious freedom are real and growing rapidly.

- The biggest risks may be in the social arena as cultural forces characterize those with traditional beliefs as bigots.

- We should determine what is essential to maintain religious freedom and become involved politically and socially to defend it.

“Although the vast majority of Americans are willing to let others believe and worship as they choose, the sphere for the free and open exercise of religion is shrinking as society grows more indifferent toward religion and as government enforces secular values in areas once considered private.” —Elder Lance B. Wickman, emeritus General Authority Seventy

Religious freedom is a fundamental human right that’s essential to mortality’s central purpose of exercising divinely granted moral agency to make righteous choices that lead to eternal life.

That was the driving message of Elder Lance B. Wickman’s July 7 keynote address at the 2016 Religious Freedom Conference at Brigham Young University. The annual gathering brings together lawyers, law scholars, writers, and public affairs specialists for two days of vigorous discussion on the complex issues and challenges facing religious freedom in the United States and beyond.

An emeritus General Authority Seventy and the Church’s general counsel, Elder Wickman called religious liberty “the cocoon” in which such agency develops and thrives.

“It provides meaning and purpose to our families and relationships,” he said. “It provides hope and assurance that this mortal sojourn, so often fraught with pain and sorrow, is not the end but only a step toward a glorious hereafter.”

When religious freedom is respected as a fundamental right, he added, laws and societies afford people the space they need to live their deepest beliefs freely and openly.

Religious freedom is not absolute. Limitations are necessary to protect life and property or to protect infringements upon the rights of others. “But any limitations should be truly necessary and not an excuse for abridging religious freedom.”

Elder Wickman warned that threats to religious freedom are real and growing rapidly.

“Although the vast majority of Americans are willing to let others believe and worship as they choose, the sphere for the free and open exercise of religion is shrinking as society grows more indifferent toward religion and as government enforces secular values in areas once considered private.”

A major flash point, he said, is the ongoing sexual revolution and the increasing use of nondiscrimination laws to force acceptance of secular views of marriage, family, sexuality, and gender that conflict with important religious beliefs and ways of life.

On other fronts, some ethics and licensing bodies seek to discipline professionals who espouse traditional sexual mores.

“It may soon be hard to be a faithful Church member who openly believes in the family proclamation and to be a psychologist, social worker, or even a lawyer,” he said. “Openly holding such beliefs is already difficult socially within professional circles, but it may soon be difficult as a matter of ethics and licensing. I’m aware of a recent situation where a state occupational board opened a formal investigation into an LDS counselor for things he said as a member of his stake high council.”

Elder Wickman noted that the biggest risks may be in the social arena as cultural forces characterize those with traditional beliefs as bigots.

“Traditional believers and their religious institutions may eventually be relegated to pariah status—officially recognized as ‘equal citizens,’ while in practical reality marginalized and penalized for their faith.”

The Constitution’s First Amendment protects core elements of religious freedom rights such as the freedom to express religious beliefs in word and writing. Parents remain free to pass their faith on to their children, and churches can form their doctrine and leadership without government interference.

But the First Amendment leaves unclear how to apply religious freedom to other areas of life such as, say, if a religious doctor has the right not to perform a medical procedure that violates his or her conscience, or if a tax deduction is guaranteed on contributions to churches and other religious organizations.

Such ambiguities in the meaning of the First Amendment is not a defect, he said, but a constitutional design. The Constitution secures the core “of our most basic rights,” while establishing a democratic process for resolving difficult issues or rights and social policy.

“Sometimes we seem to think that the Supreme Court ought to decide all the really important issues by turning everything into a ‘right’ and then balancing out competing rights in the way it thinks best,” he said. “But such thinking only cheapens our democracy and our citizenship. The Founding Fathers intended our system of representative democracy to be a framework for resolving fundamental clashes of opinions about matters of vital importance, not just about where to locate the town post office.”

Those who care deeply about religious freedom have two important duties: first, set priorities that make clear what is core to religious freedom and what is less vital, and second, get involved politically and socially to both defend religious freedom and to make appropriate compromises to ensure peace and fairness.

“Defenders of religious freedom have to decide what is closer to the essential core of religious freedom and what is more peripheral. To do otherwise risks weakening our defense of what is essential,” he said.

Elder Wickman identified several nonnegotiable “freedoms” that define the core of religious liberty: freedom of belief; freedoms related to family gospel teaching and worship; freedom to express beliefs to another willing listener, such as in missionary work; and freedoms related to the internal affairs of churches—including the establishment of church doctrine, the selection and regulation of priesthood leadership, and the determination of membership criteria.

He added that there should be no religious test for working in the various professions regulated by government. “Those with traditional beliefs regarding marriage, family, gender, and sexuality should not be excluded from being professional counselors, teachers, lawyers, doctors, and any other category of occupation where the government grants licenses. Nor should it be more difficult to establish a nonprofit religious organization than a secular nonprofit.”

The government should also avoid using its ability to fund education to coerce or pressure religious schools into abandoning their religious standards.

There are zones where claims of religious freedom are weaker and difficult to defend, said Elder Wickman. “If it is your job to perform marriages for the county clerk’s office and no one else can easily take your place, then your freedom to refuse to perform marriages that are contrary to your religious beliefs may be very limited.”

To preserve religious freedom and live in peace in a society increasingly intolerant of faith “we will have to be very clear about what matters most and make wise compromises in areas that matter less. Because if we don’t, we risk losing essential rights that we simply cannot live without.”

Elder Wickman concluded with a call for both courage and civility.

“Stand firmly for principle while understanding that in some areas we will have to compromise to protect our most vital freedoms.”

Elder Lance B. Wickman, general counsel of the Church, gives his keynote speech at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

George Monsivais takes notes at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at the BYU International Center for Law and Religion Studies in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

A Religious Freedom Conference pamphlet is seen at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

Bill Atkin applauds at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

Steven Hoskins looks over a pamphlet at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

Elder Lance B. Wickman greets a conference-goer at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

Elder Lance B. Wickman, left, talks with Matthew S. Holland, president of Utah Valley University, at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

Matthew S. Holland, president of Utah Valley University, gives a speech at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

Matthew S. Holland, president of Utah Valley University, answers questions after his speech at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

Ramona Siddoway listens to a presenter at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

Lowell Castleton talks during lunch at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

Jennifer Alvord talks during lunch at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

Michael D. Frandsen, director of Public Affairs for the Church, gives a presentation on how to effectively discuss religious freedom at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

Deanne Nordin, left, and George Simons, center, talk with Michael D. Frandsen after his presentation at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

Nannette Redo attends the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

Kathleen Hall takes a picture of a slide during a presentation at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

Lana Lichfield asks a question at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

Conference-goers are seen during a break at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.

Natalie Robison, right, talks with a fellow conference attendee during a break at the Religious Freedom Annual Review at BYU in Provo, July 7, 2016. Photo by Hans Koepsell.